LE PAVILLON BLANC

plays

FICTION

with

Pocket Genealogy of the Supreme King

At Colomiers in the Toulouse agglomeration, in the Médiathèque and the Centre d’art de Colomiers designed by Rudy Ricciotti, Le Pavillon Blanc has made encounters between the visual arts and literature the crucible of its cultural identity: narrative, fiction, graphic design and comic strip cross paths with art. Le Pavillon Blanc invited the author Philippe Vasset to write a fictional piece based on the work of the comic strip author David B., on exhibit from 26 September 2015 to 2 January 2016. This text will feature in an edition published by L’Association: "Portraits de mon frère et du roi du monde" [Portraits of My Brother and the King of the World].

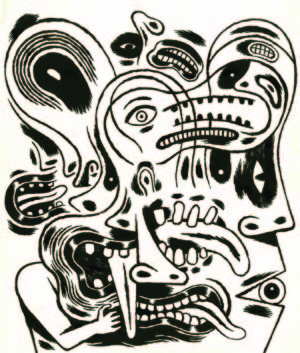

In David B’s seventy-two drawings, the King of the World is a tarot card, a rune, a number, a sign with an elusive referent, the mask of a face revealing itself.

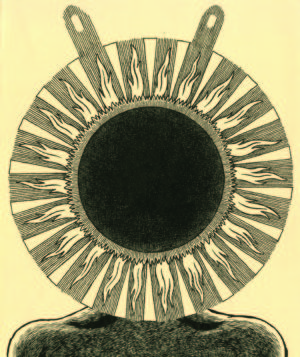

But the King of the World is not just an image. He is also a man, whom some people have met. In the late 19th century one of these lucky few, who has remained anonymous, confided his experience to Joseph Alexandre Saint-Yves, a naval officer, seaweed farmer and adept of the occult. Saint-Yves recorded these revelations in a short book, Mission of Europe in Asia, in which, amongst other things, he recounts that a secret society, Agarttha, stemming from the ancient empire of Ram, lived dispersed in deep caves throughout the world. The supreme head of this mysterious alliance was the Brahātmā, “support of souls in the Spirit of God,” holder of a primordial esoteric knowledge. “During these ceremonies,” Saint-Yves continues, the Brahātmā is “seated on a white elephant. From his tiara to his feet, he shimmers with a dazzling light that blinds all eyes. On his chest, the rationale blazes with the fire of symbolic stones dedicated to the celestial zodiacal Intelligences and, like Aaron and his successors, the Pontiff can repeat the marvel of spontaneously lighting the sacred flame on the altar at will. His tiara with seven crowns surmounted by holy hieroglyphs expresses the seven degrees of the descent and reascension of the soul through the divine Splendours that the Kabbalists call the Sephirot.”

Thanks to his priceless informer, Saint-Yves pierced this blazing screen and gave a full-length portrait of the figure: “His ascetic, elegantly boned body is solidly muscled. At the top of one arm three narrow symbolic bands stand out. And above the rosary and the white shawl descending from his shoulders to his knees, there is one of the most remarkably characteristic heads. Its features are of extreme finesse. Although the teeth are habitually clenched in great concentration of intelligence and will, the mouth has benevolent lips, on which floats the inner radiance of an unchanging charity. The chin is small but prominent enough to convey energy, confirmed by the aquiline nose. The spectacles allow a glimpse of well-shaped eyes, as steady and deep as they are good. But the eyes, which generally harden any physiognomy, give this one great gentleness combined with true power. The forehead is enormous, the head is partly bald. From this Magus-Pontiff’s entire person there emanates an absolutely outstanding aura.”

To read this extraordinary description one has to descend into the basement of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, because as soon as Mission of Europe in Asia left the press its author, scared by the consequences of his revelations, destroyed almost all the copies. When he died in 1909, Saint-Yves bequeathed his notes to the esoteric René Guénon who, distrusting the adventurer’s sources, did nothing with them. So for some fifteen years, Saint-Yves’ notebooks gathered dust on a shelf.

It took the publication of a book, Beasts, Men and God, by another adventurer, Ferdynand Ossendowski, in 1924, to stir Guénon from his inactivity. A Polish geologist and chemist, Ossendowski was a university professor in Omsk when Lenin and the Soviets seized power in Moscow. Involved with the tsarist groups who were fighting the Bolsheviks, Ossendowski had to flee for his life and travelled to British India via Mongolia and Tibet. During his journey, he recorded accounts in every way identical to Saint-Yves’ stories: a secret society, Aghartta, hidden in tunnels dug throughout the world, holder of cosmic mysteries and whose invisible and mysterious head was the “King of the World” (Ossendowski is the first to use this term). Struck by the concordances between the two accounts, Guénon wrote a short study on the subject in 1927. But Guénon was an intellectual, for whom there was no question of giving the slightest credit to any such personification of the King of the World. According to him, such a figure simply did not exist and was merely a symbol of a primordial and supreme legislator, whose history he traced in ancient mythologies.

But this purely conceptual approach was by no means accepted by all. Having observed me daily retrieving the writings of Saint-Yves, Ossendowski and Guénon from the Bibliothèque nationale’s librarians, a plump little man approached me at the institution’s coffee machine. Apologising for his indiscretion, he said he could not help noticing that I was consulting very rare, very fascinating books… I acquiesced cautiously, manoeuvring my stirrer in the steaming beaker dispensed by the machine⎯I have aversion to amateur occultists and their unbearable verbiage. But this little man was different: he went on conversing, informing me amongst other things that Ossendowski had crossed the zigzagging path of Baron Ungern-Sternberg, nicknamed the “Mad Baron,” who dreamed of reigning over the steppes and was so strikingly portrayed by Hugo Pratt in Corto Maltese in Siberia. The conversation was slow and pleasant. My interlocutor, wearing a hound’s-tooth jacket and buttoned waistcoat and with his face was framed by white sideburns, reminded me of a Cluedo character. We conversed, watching dusk descend on the library’s inaccessible central garden. No longer feeling like going back to my desk, I now had a yearning to drink something other than industrial coffee. Colonel Mustard could think of nothing better. “But not here⎯there’s nothing up there on the plaza. We’ll have to cross the river. I’ll show you the way.”

We took the escalator up to the great concrete lid over the public reading rooms. The trees in the garden below reached the level of the square. The black birds swirling above their tips were regularly diving into the pit of greenery with shrill calls. My companion gestured to the Passerelle Simone de Beauvoir spanning the Seine. We crossed it in silence, struggling against the icy wind on the river. On the other side, we entered the former Bercy wine warehouse complex. My guide knew where he was going, turning right then left until we arrived in front of a small bar in a former wine cellar. The walls were panelled with old wine casks and, ignoring the municipal ban, there was a fire blazing in the fireplace. The place was narrow, warm and glowing, a blessing after the glacial wind. We ordered a carafe, drank the first glass without saying much, then he tried again: so, what could interest me in these ancient stories? I explained that I was writing a text on a series of portraits by the comic book artist David B. I took a folder out of my bag and produced several reproductions. He examined them closely, pointing out occurrences, details that pleased him. “The series is called Portraits of the King of the World,” I concluded. “So there you have it in a nutshell.” “Why this title?” he asked me. I told him about the theory I wanted to develop in the text, that for David B doing these drawings had been a kind of ceremonial, an attempt to lay bare a mysterious, protean entity by stripping away its masks one by one. “So the 72nd and last portrait is that of the King?” he asked. “That’s what I think. It’s a psychic representation, of course, but it’s definitely him. You see the featureless face, blurred by avatars, and the glasses, not on the eyes ⎯there aren’t any⎯but on the forehead, the seat of knowledge. The King of the World has no face, he could be anyone. What distinguishes him isn’t visible: only initiates can recognise him. The others remain blind.”

The barrage of questions ceased. The only sounds now came from the crackling fire and the muffled conversations at the surrounding tables. I finished my glass and made to get up to leave but he placed a chubby hand pockmarked with blond spots on my forearm. “Stay. You’ve given the subject a lot of thought.” What did he know? I was growing tired of his mysterious, insinuating airs. He smiled, which only exasperated me even more. “Calm down and have another glass of wine. You’re thinking right but you’re seeing nothing. For you, all this is just a story, folklore. For me, it’s something very different.” What then? Did he believe in the King of the World? Had he met him? “We’ll carry on this conversation later, you’re too restless. Why don’t you come to the Bonaparte tomorrow evening at seven⎯the café on Place Saint-Germain. I’m meeting some friends there. We’ll talk.” He produced a potbellied leather wallet, paid for the wine and handed me a card: Onésime Bougrain, retired, and an address in Montreuil. Who was this guy? “Could you lend me three of the portraits you showed me?” he asked. He wanted numbers 13, 18 and 22. I gave him the reproductions and he left me with a broad smile. I felt like an idiot: I had a text to finish and, instead of working, here I was letting myself be charmed by this nutcase. I felt quite put out on my way home.

But this did not prevent me from going to the Bonaparte the next day. I could easily pretend that I was drawn there by some unknown force, but the truth is more prosaic: I had struggled with my text all day without getting anywhere and I was dying to get out. And I had never seen occultists at close quarters, and these ones seemed singularly inoffensive. At least this is what I told myself. And so there I was in Place Saint-Germain at the appointed time. The Bonaparte had to be the unlikeliest place in the world for an occult meeting: crammed with tourists and betting shop punters rather than the secrets of the universe. Onésine, more Colonel Mustard than ever, was sitting at the back surrounded by about ten people. He greeted me, pointed to a chair. I saw that he had the three drawings in front of him, watched his hands moving from one to the other. “You see these three figures,” he said, “This is how humanity represents knowledge. Like a burning principle, illuminating every gesture. He who knows has to be this man radiating light, with words of fire and cosmic thoughts. The truth is very different. To know is not to have power. True knowledge exists only when incarnate.”

I let him talk and looked around: a few well turned-out young men, old men with eyeglass chains, two women. One of them looked like Miss Scarlett, another Cluedo character, which triggered a bout of inner giggling it was all I could do to hide. Yet I did not get up and leave. As with the previous day’s conversation, there was something strangely amusing about Onésine’s verbiage. Some of it made sense. I quietly asked the woman next to me who he was. “Onésine?” she whispered. “Why he’s the Boss!” I thanked her, smiling inwardly: now I knew a lot more!

But what I found most disconcerting was that the Boss talked like a Fifties actor. His sermon was riddled with outmoded expressions like “up the creek without a paddle,” “muggins” and “he was tipsy!” It was both derisory and moving, and completely offbeat in a mystical context. I kept pinching myself, wondering what I had got myself into, but I stayed put. And nobody else left either. The bar began to empty but they kept serving us and Onésine went on holding forth. I was surprised that I was not bored. Then eventually at two o’clock the café’s shutters came down and we had to leave. I left with Onésine. “So you’re the Boss then, are you?” I quipped. “Which is better than King, don’t you think?” he replied as quick as a flash. “It’s more modern.”

I thought I had heard him wrong. Now he was laughing: “Now do you understand why yesterday I said you weren’t seeing anything? You were theorising about a principle, without seeing the principle right in front of you!” He was even crazier than I thought. Nevertheless I wanted to test his logic: “Okay, so if you’re the King of the World then where’s your tiara, where are your diamonds, your elephant?” He stopped me gently. Hadn’t I heard what he was saying earlier? True knowledge has no attribute. I had said it myself: the King of the World could be anyone.

So what about the tunnels, the caves, the ceremonies? “They exist, don’t worry, even if they have nothing to do with your idea of them.” If they were in Montreuil then we were indeed a long way from the Himalayas… He stopped. “It’s surprising how you think right and talk wrong. You know that he who knows can do nothing about it, yet you continue as if you thought the contrary. The King of the World does not reign. He embodies supreme knowledge, the Principle. It’s only inside that he’s different. On the outside he’s like you and me – in this case, like me.” I had a broad mind, but not broad enough to accept a King of the World in Montreuil: why not Saint-Chamond? And where were the guardians charged with protecting him? “Who needs protection when the very ones who know don’t want to recognise me? I’m safer than any of my predecessors ever were.” He shook my hand and disappeared.

I still have his card, and of course I went and checked the address: a pretty suburban house in an anonymous street. I wanted to ring the doorbell but thought better of it. What was the point when I did not believe? But I did go and look at the portraits of Ossendowski, Saint-Yves and Guénon. And all those adventurers of the occult looked like stamp collectors.

Philippe Vasset

Translation : David Wharry