THE CNEAI= CENTRE NATIONAL EDITION ART IMAGE

plays

OBLIVION

with

Elie During

Elements for a diagram

Dedicated to media works, since 1997 the Cneai has been transforming in line with artistic desires and necessities: creating a collection of editions and multiples (600 editions), building the FMRA collection (11,000 artist publications), commissioning the "Floating House" (an artist residence on water) from the Bouroullec Brothers, renovating Maison Levanneur with architects Bona & Lemercier in 2012. In the context of the Cneai's new programme, which alternates exhibition Scenarios and inaugural Festivals, Elie During presents his personal interpretation of the place by exploring memories of his visit.

Click here to download the diagram.

Elie During, “Eléments pour un diagramme”, May 2013, graphic design: Himmelsbach and Kaës.

From museum to home

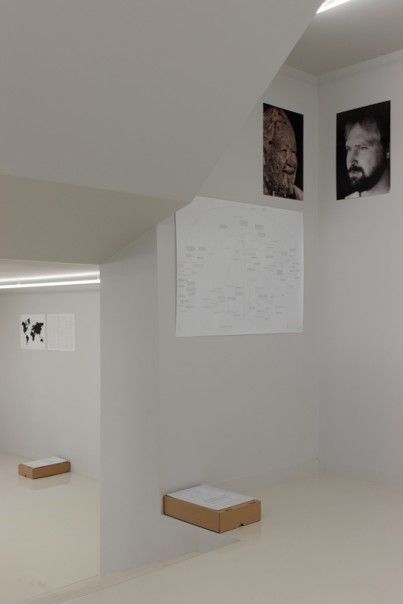

Spending an afternoon at Centre national édition art image [National center for art publishing and image], on Chatou’s Impressionists island, feels more like visiting a private home rather than an exhibition. This is not only because of the architecture of the place and its surroundings – the piece of garden, the barge -, but more fundamentally because the way things are displayed – not only properly hung on the walls, but also leaning against them, resting on shelves, lying on pieces of furniture – are a very concrete evidence of the continuous activity of those who are toiling, within these walls, to organize and expand a collection while collaborating with the artists. Indeed, we’re visiting a house in Chatou (the Levanneur House) which is, from the ground floor to the attic, a workshop or a factory where art is thought through and exhibited in innovative formats that are constantly matching ways of circulating art in the age of mechanical reproduction: prints and books, but also posters, newspapers, notebooks, envelopes, maps, models, LPs, slides, etc.

Spending an afternoon at Centre national édition art image [National center for art publishing and image], on Chatou’s Impressionists island, feels more like visiting a private home rather than an exhibition. This is not only because of the architecture of the place and its surroundings – the piece of garden, the barge -, but more fundamentally because the way things are displayed – not only properly hung on the walls, but also leaning against them, resting on shelves, lying on pieces of furniture – are a very concrete evidence of the continuous activity of those who are toiling, within these walls, to organize and expand a collection while collaborating with the artists. Indeed, we’re visiting a house in Chatou (the Levanneur House) which is, from the ground floor to the attic, a workshop or a factory where art is thought through and exhibited in innovative formats that are constantly matching ways of circulating art in the age of mechanical reproduction: prints and books, but also posters, newspapers, notebooks, envelopes, maps, models, LPs, slides, etc.

Now, this is the real beauty of it all: these means of circulation are effective on the spot since any visitor can purchase, for a fair price, a book or a print that he likes. Sometimes he only needs to pick something up: LIBELLE°, the double-sided posters commissioned by Alexandre Baudelot, a 1300 copies prints sealed in their flexible envelopes, are one of the many examples of forms that the «economy of giving» can take in such a context.  While leaving the Impressionists island, one does not bring back the grand catalogue acting as a trophy of our participation to the exhibition event, either directly or remotely. Instead, we’re bringing home fragments of the place itself, like you would take a stone from an archaeological site to add to your personal collection. Whether they will be added to a treasure or passed along to people you meet, these fragments of art – that don’t need to be called artworks – are acting, above all else, like the elements of a tangible memory of having been there. Together, they’re setting up the marks or milestones of what could be the diagram of an exhibition that would be, by essence, virtual. Something like taking sample or drawing a cross-section of the process.

While leaving the Impressionists island, one does not bring back the grand catalogue acting as a trophy of our participation to the exhibition event, either directly or remotely. Instead, we’re bringing home fragments of the place itself, like you would take a stone from an archaeological site to add to your personal collection. Whether they will be added to a treasure or passed along to people you meet, these fragments of art – that don’t need to be called artworks – are acting, above all else, like the elements of a tangible memory of having been there. Together, they’re setting up the marks or milestones of what could be the diagram of an exhibition that would be, by essence, virtual. Something like taking sample or drawing a cross-section of the process.

Memories of a spectator

In that respect, the experimentation held in Chatou carries an exemplary value. By changing radically the coordinates of the problem at hand, by creating a new relationship between the place and the works it’s telling us something about our relationship with the exhibitions in their ordinary form. Because, in the end, the goal is always to conjure up, through the combined powers of memory and oblivion, a kind of personal diagram that no catalogue, no monographic documentation, will make up for. Paul Valery’s rantings and ravings against the museum are still very much topical. How to avoid saturation, the reciprocal neutralization of the works unavoidably induced by the gathering, on a same location, of rich and sometimes unfathomable artistic universes?

A first solution would be the one used by the curators, as often as they can: to open the way for a journey, allowing the visitor a certain amount of liberty of movement in the hope that, along a wandering setting, fruitful associations will be born. This can work: you have to see it first hand to judge. And it’s not impossible that reading the catalogue will offer in many cases a more intense and interesting experience than visiting the exhibition itself.

And there is another side to that coin, that no one seems able to grasp. It is the experience itself, or rather what we are doing with it when we leave the exhibition. It is the natural process allowing the memory to settle. It is the shaping work we do when we try to actively recall, resizing the residues of the experiment to deliver a kind of working draft, a concentrate, a subjective precipitate. It is probably impossible to control thoroughly all the parameters of such a process, nor to know beforehand if an exhibition will be able to survive, in the visitors’ mind, in a way that is not merely a collection of vignettes of the works that would have catch their eyes one way or another. But we can at least try to make ourselves sensitive to the issue by artificially recalling this experiment. Forcing one self to mentally revisit an exhibition for instance, taking it to new grounds from the seeds of memories where our feelings are shrouded, in a condensed and nebulous state. It doesn’t matter if fake memories are sipping in: it’s part of the game. This is not an in situ reconstruction, aiming to create a «path», but a work of ex post interpolation that is kind of reminiscent with the way the archaeologist is hypothetically drawing an entire skeleton from a single fragment of vertebra.

Nebulas

«So a nebulous mass, seen through more and more powerful telescopes, resolves itself into an ever greater number of stars 1.»

Obviously, the question is not to recreate the whole event through a painstaking process of historical reenactment, mechanically adding more and more elements along the fragments documenting an earlier visit. The exercise is rather to expand the consciousness in order, granted it’s now wider and occupying several layered states, to allow a further inventory of its riches, even if it means that the final picture only vaguely resembles the seminal experiment. The picture will undoubtedly be simpler than its subject: the idea is to bring out the highlights rather that specific details. Let’s call it a «diagram» since the word already appeared several times.

How to achieve that ? It is doubtful that any fragment, any actual image, considered in the present, will give access to the memory from which the diagram develops. As Bergson states, «the image, pure and simple, will not be referred to the past unless, indeed, it was in the past that I sought it, thus following the continuous progress which brought it from darkness into light 2». The past, we need to go there first, in one swift jump, and deploy our resources from there. «Essentially virtual, it cannot be known as some thing past unless we follow and adopt the movement by which it expands into a present image, thus emerging from obscurity into the light of day. 3» A pure memory isn’t a dimmed perception, a trace or an archive in which life could be restored through perception and imagination. It required a special operation, which means that one needs to think from the past, in the direction of the past, to return to the source. It means also seeking what we keep within us from a past experience in the shape of a dynamic diagram; cells or experience nodes only waiting for an outside trigger to spread on the whole surface of consciousness their constitutive elements that only existed in a folded and indistinct form, like the Japanese paper slowly unfolding in a bowl of water.

First inventory

The tangible traces (texts and images) are obviously playing a part. But rather than documents, they are the catalysts and the starting gears of the diagramatic process.

Two months after my visit in Chatou, I unpack the plastic bag that is the evidence of both the great hospitality I received from Sylvie Boulanger and its staff, and of my interests at that time. Here is a summary inventory:

– a «Journal scénario» dated winter 2012 and mentioning the queer title chosen by Dora Garcia, «Real Artists Have No Teeth»;

– a «small journal» about the reboot of an historical project, «Art by Telephone», which includes the facsimile of a letter from Duchamp replying to Jan van der Marck’s invitation to participate in the 1969 exhibition by phoning in instructions for a work: «I find the idea quite brilliant, but do not feel like participating, for different reasons, the most important one being my state of non-activity – I don’t feel strong enough to undertake any action even by telephone»;

– copies of the first two issues of Old News, «an art project about the media and recycled news» which seems very relevant in regard to our business at hand,  since the guiding principle of this project is questioning how images from the press can exist and survive in our era of mass media;

since the guiding principle of this project is questioning how images from the press can exist and survive in our era of mass media;

– a special edition of Jef Geys’ journal Kempens – Informatieblad, an artist whose very existence I discovered during my visit at Cneai, and who still remains almost a mystery to me;

– a book from Yona Friedman published by Cneai, in which the dia – or picto – grammatic method of representation that became a signature style of the architect is used to create an illustrated version of Leibniz’s Monadology;

– a few posters made from Leonor Antunes’ «dancing grids»: like the ones that were glued in the corner of the Levanneur House’s first room;

– a copy of Simon Starling double-sided poster (Project For A Masquerade (Hiroshima) / The Innkeeper – Randy Bass) for LIBELLE°9, that I remember taking out of its envelope in the train home to look more closely at the diagram that was inside, an A2 sized navigation map created by Franck Leibovici in response to the artist’s proposal; – an issue of Jean-Quête magazine by the «Accès Local» collective, which is about a study conducted with 150 persons on the social uses of photography; this copy which was pulled out from Cneai’s own stock thanks to Sylvie Boulanger doesn’t have any pictures: it is really an unidentified graphic object, alternating interview fragments, lists, charts and diagrams, creating a greater and greater gap between it’s original material (the «stack» of mundane photographs used as a basis for the study).

– an issue of Jean-Quête magazine by the «Accès Local» collective, which is about a study conducted with 150 persons on the social uses of photography; this copy which was pulled out from Cneai’s own stock thanks to Sylvie Boulanger doesn’t have any pictures: it is really an unidentified graphic object, alternating interview fragments, lists, charts and diagrams, creating a greater and greater gap between it’s original material (the «stack» of mundane photographs used as a basis for the study).

Diagrams

The gathering of these documents, like a core sample, testifies of the diversity of projects associated with the various temporal layers within Cneai. For me, they are the material ground that will allow some embryos of memory to blossom into diagram elements, through a-chronological associations that probably won’t have anything to do with the one explicitly used within the logic of production, but that would unmistakably met some of my problems, which might not even be related to art.

For instance, while I’m writing these lines, I vividly remember the poster with the series of Bruno Munari’s images that were first published in 1944 for Domus: «Ricerca della comodità in una poltrona scomoda» («Seeking Comfort in an Uncomfortable Chair»). This poster is the starting gear of the «Reading Dance» display, with Leonor Antunes’ geometrical grids I already wrote about, and also one of Erwin Wurm’s «One Minute Sculpture». When reading the «Journal Scénario» afterwards, I remember that I took a long time handling Yann Sérandour’s «Sextodecimo», a poster turned into a 32 pages leaflet through a series of folds and binding; I remember thinking that this way of doing was very smart, a minimal transformation was shuffling and redistributing the series of photos making the act of reading rather difficult, like a direct echo to Munari’s contortions on his uncomfortable chair. From one work to the next, connexions are starting to occur; I started dreaming of a film sequence that would be reedited in the same way, according to the fold rather than the cut, allowing if to be deployed in the space. Isn’t it what the video artists are doing when they use multiple projections on architectural features and walls?

For instance, while I’m writing these lines, I vividly remember the poster with the series of Bruno Munari’s images that were first published in 1944 for Domus: «Ricerca della comodità in una poltrona scomoda» («Seeking Comfort in an Uncomfortable Chair»). This poster is the starting gear of the «Reading Dance» display, with Leonor Antunes’ geometrical grids I already wrote about, and also one of Erwin Wurm’s «One Minute Sculpture». When reading the «Journal Scénario» afterwards, I remember that I took a long time handling Yann Sérandour’s «Sextodecimo», a poster turned into a 32 pages leaflet through a series of folds and binding; I remember thinking that this way of doing was very smart, a minimal transformation was shuffling and redistributing the series of photos making the act of reading rather difficult, like a direct echo to Munari’s contortions on his uncomfortable chair. From one work to the next, connexions are starting to occur; I started dreaming of a film sequence that would be reedited in the same way, according to the fold rather than the cut, allowing if to be deployed in the space. Isn’t it what the video artists are doing when they use multiple projections on architectural features and walls?

This is already the start of a diagram. I may elaborate on it some day. But did I really see Wurm’s «One Minute Sculpture»? I remember it had something to do with philosophy books. But what was it all about exactly? I can’t remember. There is like a gap there, surrounded by a vague humorous atmosphere. Documentation not only induces memories, or fake memories. It doesn’t only reveals the condensation points; it also reveals the gaps and the losses. Another example: I have no accurate memory, I realize it now, of the 14 photos poster of an abandoned skateboarding ramp that Johannes Wohnseifer laid out according to Munari’s poster. But I must have seen it however, since it is described in the «Journal».

In the same way, I only have a very blurry memory of the exhibition «Art by Telephone… Recalled» (a proposal by Sébastien Pluot and Fabien Vallos through a research program led by Angers’ Art School and several other institutions),  even though there are a few names and circumstances that are sticking out, and who are maybe the essential articulations after all, the active connections with the issues I’m working on. It’s like all of my attention span was fixed on the first occurrence, remembered («recalled» meaning also just that), the 1969 exhibition, a milestone in conceptual art which is evoked, along with other documents gathered in one of the first floor spaces, by signed letters and telegrams from and to the participants. One can be led to believe that the works recreated from the sound records, testimonies and existing documents are quieter than the archive itself. But this stealth and somewhat evanescent condition, heighten by the curating choices, is obviously at the core of the original project, that was often mistakenly reduced to a pure conceptual proposal unable to achieve an exhibited state.

even though there are a few names and circumstances that are sticking out, and who are maybe the essential articulations after all, the active connections with the issues I’m working on. It’s like all of my attention span was fixed on the first occurrence, remembered («recalled» meaning also just that), the 1969 exhibition, a milestone in conceptual art which is evoked, along with other documents gathered in one of the first floor spaces, by signed letters and telegrams from and to the participants. One can be led to believe that the works recreated from the sound records, testimonies and existing documents are quieter than the archive itself. But this stealth and somewhat evanescent condition, heighten by the curating choices, is obviously at the core of the original project, that was often mistakenly reduced to a pure conceptual proposal unable to achieve an exhibited state.  The regret to have passed by to quickly is somewhat soothed by the consolation of being able to access the recordings and documentation of the project online (www.artbytelephone.com).

The regret to have passed by to quickly is somewhat soothed by the consolation of being able to access the recordings and documentation of the project online (www.artbytelephone.com).

The experience of the exhibition also implies that you can pass right through it, without noticing it in a way. But that being said, it doesn’t mean that you cannot have a time-delayed relationship with it – a relationship that is often directly feeding the diagrammatic process.

Documented in the folders displayed on a table, a particular episode turns into an allegory: it is the exchange between Jams Lee Byars and Alain Robbe-Grillet about a phone appointment scheduled on November 13th 1969 for about thirty seconds of silent conversation. If I understand correctly, this conversation never took place. However, it feels very much like I heard it.

Click here to download the diagram.

Elie During, “Eléments pour un diagramme”, May 2013, graphic design: Himmelsbach and Kaës.

Further reading:

Cneai, centre national édition art image

Elie During

Notes: