LA GALERIE - CENTRE D’ART CONTEMPORAIN DE NOISY-LE-SEC

plays

DISTANCE

with

Sinziana Ravini

Dear Sinziana v. Dear Emilie

In 2014, La Galerie is celebrating its 15th anniversary. For over a year, the centre d’art has been growing in time with the seasons, by following the “Forms of Affects”. In June 2013, its director Emilie Renard began a correspondence with curator and art critic Sinziana Ravini, about where affects stand in art. Whereas in science, researchers have a duty to maintain an objective, neutral attitude, art critics and curators position themselves differently when they undertake their research. Then the question is: for authors—be they artists, curators or critics—, is there a distance between research and autobiography?

from: emilie renard

to: Sinziana Ravini

date: 7 June 2013, 6:08 pm

re: Transfusing massive energy from one wild beast to another might kill them both.

Dear Sinziana,  First of all, the subject I’m working on for the coming season at La Galerie is the place of affects in art. Literally what affects us is what touches us, what mobilises

First of all, the subject I’m working on for the coming season at La Galerie is the place of affects in art. Literally what affects us is what touches us, what mobilises

– or, on the contrary, immobilises – us. To address art from this angle, by trying to identify the ‘forms of affects’, is to try to understand how they function as immersion factors in relation to artworks, forms of affects being a means of locating both the place moved into by the artist and the one occupied by the viewer.

Your own affective and subjective position is perceptible in your work as a curator; sometimes it takes on near-expressionist form in that there’s a clear proximity between your biographical input and what you’re out to achieve. The aim of this conversation is to look more closely at this concept and see how you put it into practice.

I’d like to begin with a work by Mike Kelley whose title alone speaks volumes: More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid (1987). The stuffed dolls it’s composed of are strange half-human, half-animal bodies, in most cases gifts from mothers and grandmothers who have worked on them lovingly for hours and hours. As the title says, there’s no monetary equivalent of these hours of love. Kelley takes an emotionally charged non-professional practice and turns it into a cumulative, agglomerative, overflowing, saturated work that reveals something suffocating – a surfeit of love. In a conversation with John Miller in 1991 Kelly spoke of this surfeit and the implicit obligation for the receiver to reciprocate: ‘Basically, gift giving is like indentured slavery or something. There’s no price, so you don’t know how much you owe. The commodity is the emotion. What’s being bought and sold is emotion. I did a piece called More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid. I said if each one of these toys took 600 hours to make then that’s 600 hours of love; and if I gave this to you, you owe me 600 hours of love; and that’s a lot. And if you can’t pay it back right away it keeps accumulating 1…’

Here I’m starting you – you who created the exhibition titled The Hidden Mother (2012) – on an approach to affect manifesting itself as almost pathetic filial love. And I’m doing it with a question: does the affective charge slide, with almost no loss of intensity, from the initial object (the soft toy made by the mother) to the work of art (made by Kelley)? Of course you may want to talk about other transitional objects…

Looking forward,

from: Sinziana Ravini

to: emilie renard

date: 17 June 2013, 4:09 am

re: Transfusing massive energy from one wild beast to another might kill them both.

Dear Emilie,

I began my career in the art world writing stern, argumentative stuff for the Swedish art magazine Paletten, where I became joint editor-in-chief with Fredrik Svensk. My idols at the time were the theoreticians from October. I wanted to be like them: no feelings, even fewer doubts, telling it like it is.

Now I think the big issue of our time is the complete opposite of all that, the need to reclaim art discourse for the emotional domain, that mysterious theatre of the unconscious that’s there whether we like it or not. But to do that you have to be ready to expose yourself, lose your way, make mistakes and most of all, exaggerate. I adore thinkers like Slavoj Žižek, who manage to dramatise their ideas with their bodies, their sweat, grand gestures and above all, jokes. In that context there’s no problem in talking about emotional expressionism, but I also like thinkers a tad more sophisticated, like Simon Critchley. In his book Very Little… Almost Nothing (1997) he attacks contemporary nihilism in a beautifully simple introductory account of the death of his father. It’s terribly moving to enter a philosophical world through this emotional prism. How does he manage to speak so frankly of his father and then bring such finesse and complexity to his discussion of world philosophy? Every time I reread this passage I’m baffled. Ever since, I’ve tried to begin everything I write with a personal story, an admission or a speculation unrelated to the actual text, as if I were stretched out on an analyst’s divan and letting the words pour out unadorned.

Of course, working with affect is a form of manipulation. But honest manipulation: at least that way the desire of the person writing or speaking becomes a desire truly laid bare and, in an ideal world, analysed.

Reading back over what I’ve just written, I realise I’ve fallen into my own trap. I set out to talk about affect, about emotional expressionism and all the other things you mentioned, but I’ve done it too abstractly. Maybe it’s time to really throw myself into the subject and speak of a work that touched me very deeply and was the triggering factor for my exhibition The Hidden Mother.

One winter day I was in a gallery in Stockholm and saw a film that set the whole project in motion: it was the story of three women – a daughter, a mother and a grandmother – whom you first see making up in front of the mirror in a theatre dressing room. They’re abusing each other verbally, the mother attacking the grandmother while the daughter looks on sadly. In the next shot they’re on stage and beginning to talk about their shared history, their fears and regrets. The mother accuses the grandmother of not having been there for her when her father committed suicide: “Do you understand?” she says. “When I lost my father I lost you too. I lost two parents at the same time.” The grandmother explains that she couldn’t help because she’d been taking massive doses of Prozac so as to cope with the suffering. All this time the daughter is watching them and trying to make contact with her mother, but it’s impossible. Too obsessed by her own suffering, the mother hardly looks at her. We realise that history is repeating itself: Tova Mozard, the artist who has brought her own mother and grandmother on stage with her, will never get free of the affective curse that locks them all into their own emotions, to the point where none of them can see the world as it really is anymore. At that moment I burst into tears… I hadn’t cried for a very long time.

One winter day I was in a gallery in Stockholm and saw a film that set the whole project in motion: it was the story of three women – a daughter, a mother and a grandmother – whom you first see making up in front of the mirror in a theatre dressing room. They’re abusing each other verbally, the mother attacking the grandmother while the daughter looks on sadly. In the next shot they’re on stage and beginning to talk about their shared history, their fears and regrets. The mother accuses the grandmother of not having been there for her when her father committed suicide: “Do you understand?” she says. “When I lost my father I lost you too. I lost two parents at the same time.” The grandmother explains that she couldn’t help because she’d been taking massive doses of Prozac so as to cope with the suffering. All this time the daughter is watching them and trying to make contact with her mother, but it’s impossible. Too obsessed by her own suffering, the mother hardly looks at her. We realise that history is repeating itself: Tova Mozard, the artist who has brought her own mother and grandmother on stage with her, will never get free of the affective curse that locks them all into their own emotions, to the point where none of them can see the world as it really is anymore. At that moment I burst into tears… I hadn’t cried for a very long time.

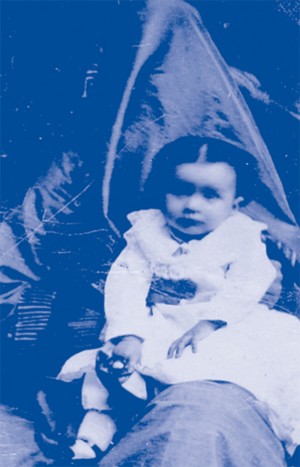

Thinking back on this later, and trying to understand why this work had touched me so deeply, I saw that it had brought me back to my personal history, to a mother who had abandoned me, or given me – there’s always a gift in abandonment – to my grandmother, who then took her place as my mother. When I saw the film my grandmother, who had been everything to me, my whole world, had just died… a year before, actually, but it was still like yesterday. My grandmother’s death had left me infinitely saddened, but this sadness had made me opaque, impervious to anything that reminded me of my real mother. That film, The Big Scene, awakened me and gave me the idea for an exhibition that would be a search for my hidden mother. I said to myself, no matter if I can never bring my mother and grandmother together on life’s stage one last time, the important thing is to bring them onto the stage of my interior theatre; but for that I had to reach out towards reality – not just the unconscious, but towards real life, in the direction that frightens us the most.

The Hidden Mother involves both these movements: on the one hand I started a double psychoanalysis, with my producer of the time, so as to talk and travel through the works in the exhibition. Later we began writing to each other, ‘homegrown self-analyses’ based on recorded spontaneous speech. But I wasn’t satisfied. I felt that both things – talking to psychoanalysts or to each other via the works – was protecting us from the real world. So I decided to add a third element that would take us towards reality, towards action and the true emotional quest: I decided to really go looking for my mother with the exhibition in a ‘Box in a Valise’, like Duchamp, to try to touch her through the works that had touched me…

This was one of the most beautiful, most difficult experiences of my life, and I still don’t know what happened between my mother and me: the exhibition novel only touches on a part of it, but one thing I know for sure is that I would never have dared to make this journey if I hadn’t come upon that work by Tova Mozard.

Love,

from: emilie renard

to: Sinziana Ravini

date: 21 June 2013, 3:29 pm

re: extreme involvement

Dear Sinziana,

Thank you for those touching lines. I see in you a form of sincerity or honesty that is something like confiding, but not only that. Confiding – that first-person narrative about something intimate – is the grounding you adopt for your exhibition novels, with your direct narration of your homegrown psychoanalysis sessions. Confiding in your case is a kind of stylistic entry, something both winning and effective (what you call ‘honest manipulation’). Ultimately you really do lay yourself open (you mention an admission), you have a central, highly visible role (which could attract accusations of egocentrism), and most of all this entry becomes a motor for work on forms that are more than merely anecdotal.

Confiding in your case involves your highly unorthodox use of psychoanalysis – rapid, with a group of 4 (2 analysands facing 2 analysts); the aim being to check out its effects on a certain practice of art criticism and to publish the results in the novel of the exhibition The Hidden Mother. When you say you want yourself as the starting point for your projects, your notion of psychoanalysis seems pretty primal to me (as if it allowed for a spontaneous, immediate relationship with the words that ‘pour out’). In fact what you do with it is a way of saying that you’re the source of this creation of meaning, language, written forms, exhibitions, films, novels and so forth which can all be shared with others.

This starting point involving the narration of a lived experience ties in with the concept of ‘situated knowledge’ introduced into feminist debate by Donna Haraway in 1988. Situating knowledge is a way of including ‘the subject of situated knowledge’ in the voicing of the knowledge that the subject has produced, and takes account of the relationship between the seeker-subject and her quest. This concept first and foremost attacks the idea of knowledge independent of the person voicing it, her situation, her body, her biography, her context and her time. The subject of ‘situated knowledge’ can take on the role of witness and defend the partiality of her view, while also assuming her responsibility for a witnessing that does not hide behind the screen of disembodied or neutral statement. Feminism raises the issue of accessing a form of objectivity in knowledge compatible with its radical challenge to universalism. Haraway says she ‘holds out for a feminist version of objectivity’ to be looked for in what she terms ’embodied objectivity’. She often speaks of a supposedly ‘transparent’ vision mediated by instruments of visualisation: ‘a conquering gaze from nowhere’, she calls it. She goes on to introduce the importance of a partial point of view, saying that she is fighting ‘for a doctrine and practice of objectivity that privileges contestation, deconstruction, passionate construction, webbed connections, and hope for transformation of systems of knowledge and ways of seeing.’

The question of objectivity does not arise in the same way in art, but the curator and the critic are often assigned to an ideal of objectivity, a critical distance. You undercut these rules in your exhibitions with what I’d call a kind of expressionist curating.

The question of objectivity does not arise in the same way in art, but the curator and the critic are often assigned to an ideal of objectivity, a critical distance. You undercut these rules in your exhibitions with what I’d call a kind of expressionist curating.

Through affects I look into excessive closeness between creators and their quest, between artists and their work. I look into a kind of ‘extreme’ involvement, aspects of commitment that can be revealed in the form of first-person discourse, confidences and expressions of doubt, joy, boredom, etc.

Ciao Sinziana

from: Sinziana Ravini

to: Emilie Renard

date: 19 July 2013, 1:27 pm

re: extreme involvement

Dear Emilie,

Once the elective affinities between art and psychoanalysis have been recognised, the question that arises is that of the true difference between the two and how one can work with this difference. If there’s something I feel really passionate about it’s the psychoanalytical work one can perform on oneself and indirectly on others via a work of art. Whether as transmitter or receiver, we are all co-creators of works that touch us.

Why has affect become so suspect that one almost has to be ashamed of working on oneself, via a work of art, when so many artists use their own lives as their material? For instance, I just love Sophie Calle, who has been able to turn almost every event in her life into a work of art. And writers are hardly ever accused of being egocentric when they decide to deal with their own lives, whether as autofiction or not. As for philosophers, Montaigne put it very well when he said (I’m quoting from memory), ‘I work on and from myself, for there is no other realm I really know.’ If artists and writers can work on themselves, why not curators? Curatorial objectivity is a fiction, but one that maybe goes hand in hand with globalisation. Art having split up into countless parallel currents, many people feel the need for a navigator who can map the world as impartially as possible. This vertical – or rather, imperialist – thinking, which tries to grasp the world as a whole while remaining neutral, is about as interesting as the white cube. It’s been said that with GPS the terra incognita is no more; maybe so, but the same doesn’t apply to the unconscious. Deleuze and Debord both grasped the importance of linking politics and art to psychoanalysis. We can’t change the world without changing the way we perceive it.

You also have to be careful not to impose your dreams on other people. Alain Resnais’ film Life is a Bed of Roses demonstrates this very well: the man who wants to change the world by eradicating people’s dreams with a Black Mass that wipes the slate clean is the very image of a bad curator. I think we can escape the dictatorship of the creator-curator through ideas that make artists real co-creators. I think we have to address the affinity between artist and curator.

I take my inspiration from a confessional, narrative art, one close to that of the cinema and psychoanalysis, like the work of Pierre Huyghe, Boris Achour, Emilie Pitoiset, Benoit Maire, Ursula Meyer and Joanna Lombard. These artists work on the unconscious, letting us wander through their works as if we were on an afternoon stroll through a forest. The art world shows a real scorn for the human imagination, for the possibility of entering an artistic world and actually living in it without trying to unveil its mysteries. I think that an approach that tries to take its engagement with an artwork further, speculating freely about its meaning or shrinking from the impossibility of saying all there to say about it, is more involving and less didactic than all those others that go looking for objectivity in abstraction and the exclusion of affect. There’s no other way of liberating the unconscious than surrendering to unshackled, undisguised utterance, to a Virginia Woolf-style stream of consciousness. What other source is there but the self? At the same time this approach doesn’t exclude the presence of others within oneself.

Lastly, the question that enthralled me most, the one I worked on in the Black Moon show, is what is love? And how to tell a love story through an exhibition? Love is a little outmoded, and Hollywood has exploited it to the hilt, but I think that if art has something to teach us, that something is the art of loving.

With love from a tranquil terrace at the bottom of a country garden.

Further reading:

La Galerie, centre d’art contemporain

Sinziana Ravini

Notes:

- Bomb magazine, no. 38, winter 1992. ↩